AIs can perform well at all kinds of tasks, such as interpreting images or text. For example, these days deep neural networks (DNNs) get over 90% accuracy on the IMAGENET benchmark database, which requires recognition of over 20,000 types of objects in over 14 million images.

Even though today’s deep neural networks have roots in early attempts to mathematically model the human brain and nervous system, the ‘knowledge’ possessed by DNNs takes a form quite different from a human’s.

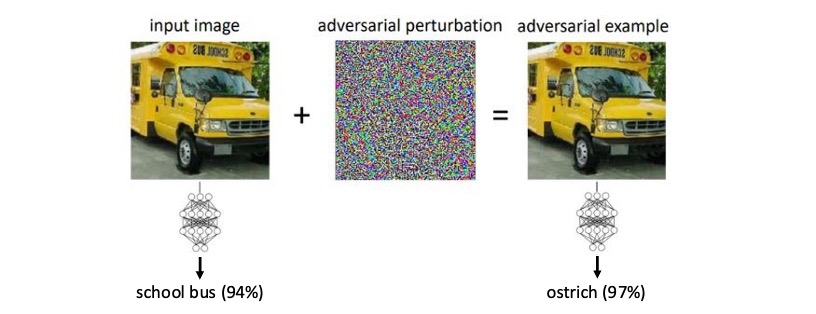

Just as a picture of a school bus is only a bunch of numbers to an AI (red, green and blue brightness levels for each pixel), an AI’s ‘knowledge’ is also only a bunch of numbers – its mathematical parameters.

Each parameter is like a calibration value, and large DNNs have billions of them. Through an exhaustive training process, millions or billions of examples are presented to a DNN, and its parameters adjusted little by little until it gets the right answers.

When kids learn to recognize that it’s a “bus” that takes them to school each morning, they gain a general concept of what a bus is – a large vehicle with lots of seats. They understand “bus” in the context of their everyday lives, with its vehicles, classrooms, classmates, and roads. This allows kids to learn what a bus is without having to see a lot of examples, and they become immediately proficient at recognizing all kinds of buses.

But to an AI, a bus is what happens when input pixel values churn through the DNN, getting multiplied and combined by the DNN’s parameters, and produce an output representing “bus”. The AI can become proficient if its training data has millions of examples of different types of buses, viewed in various contexts and from different angles and distances.

The stark difference between how humans and AI’s ‘understand’ buses has an unfortunate side effect. Researchers have discovered that AIs can be fooled by making minute changes to the numerical values of its input data, changes that are imperceptible to humans. In the example above, an AI that had been trained to confidently recognize a school bus is fooled into ‘thinking’ a bus is an ostrich. This is done simply by making small perturbations to the school bus image.

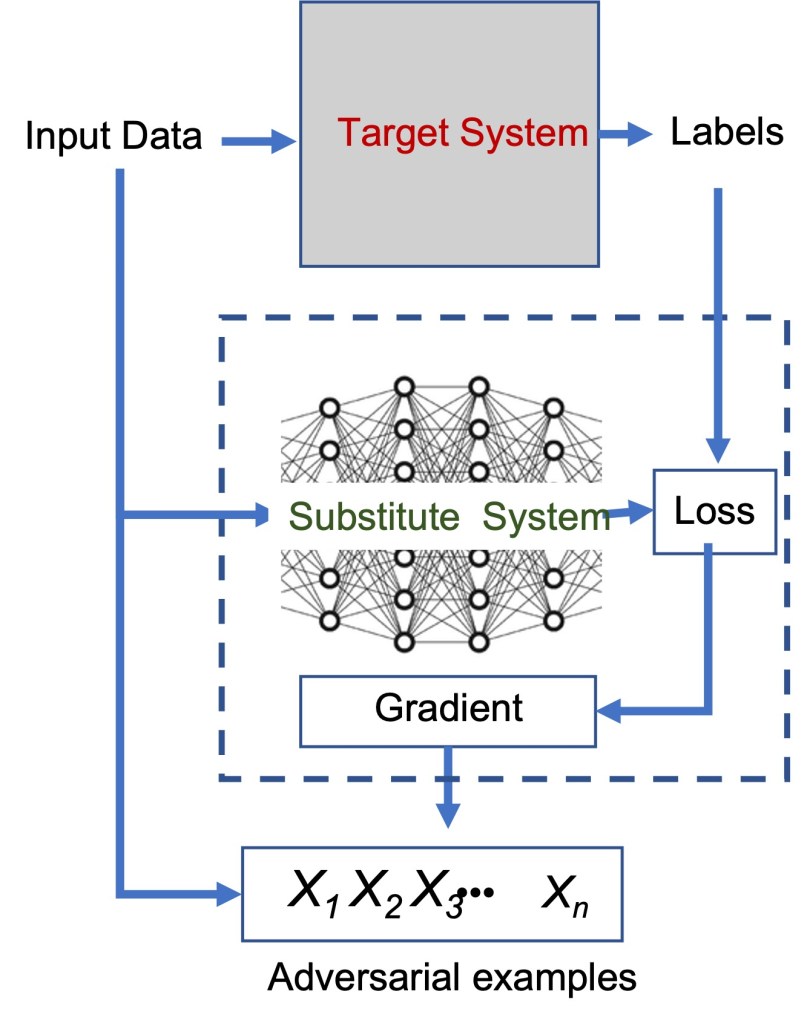

Conning an AI this way is called an adversarial attack. In the first part of my iMerit article Four Defenses Against Adversarial Attacks, I discuss why AIs are vulnerable to these attacks, how adversarial attacks can be formulated, and how such attacks can cause harm. The diagram below from the article illustrates how to devise a particular type of adversarial attack, a Black Box attack.

Black Box adversarial attack